Nuclear Retention

Case Studies and Policy Options

— Daniel Phelan

Nuclear power has historically provided baseload generation for the United States’ electric grid, and supplied roughly 19% of the country’s energy generation in 2013.11 U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2014. Nuclear offers baseload power with low greenhouse gas emissions and low fuel costs, but issues with high up-front costs and, increasingly, low wholesale electricity costs have limited the expansion of nuclear power. Existing plants that must compete with the price of natural gas in restructured markets have, in some cases, opted to shut down rather than operate at losses. The price pressures on nuclear power have placed the future of the resource under threat.

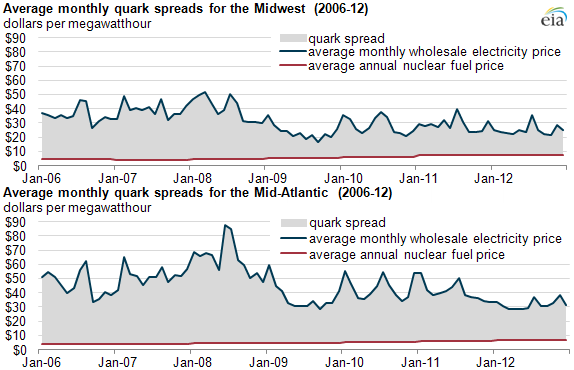

From January 2006 to January 2012, the average wholesale price of electricity in the MISO and PJM markets decreased from around $30-$40/MWh to roughly $20-$30/MWh, as seen in Figure 1 below. This has lowered the “quark spread”-the difference between the wholesale price of electricity and the cost of nuclear fuel.

Figure 1. Average Monthly Quark Spreads for the MISO and PJM Markets

It is important to note that the average fuel price, as seen in Figure 1, is not representative of all of the costs that face a nuclear generator. Nuclear plants are also seeing rising Operations and Maintenance (O&M) costs. The nuclear fleet is no longer new technology; the average age of a nuclear plant in the United States is 34 years, and 58 plants have applied for license extensions that would allow them to operate past their initial 40-year license period. Estimates have found a $10/MWh increase in non-fuel O&M costs over the 2006 – 2012 time period.22 Cooper, 2013. The combined factors of lowering electricity prices and increasing costs leave little margin for profit at plants operating in these markets.

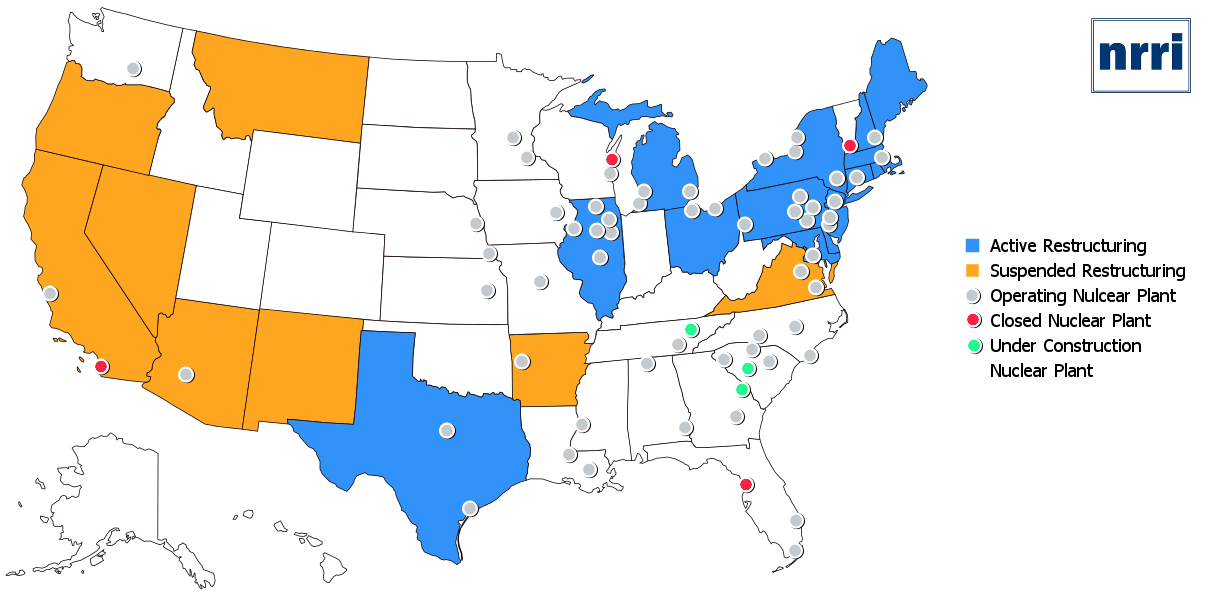

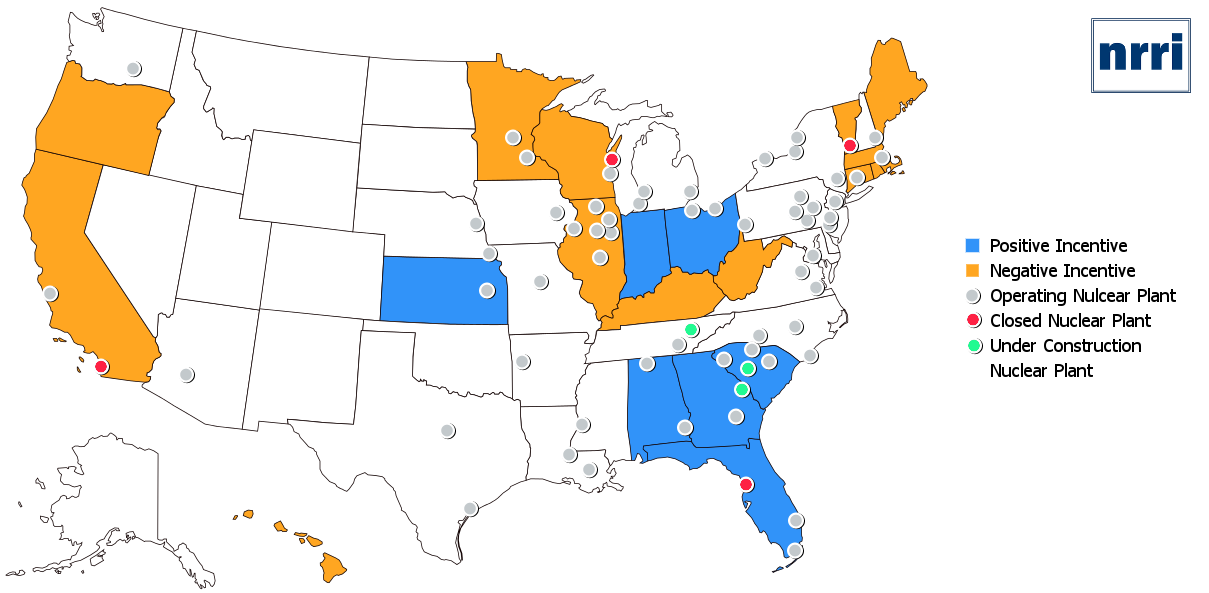

Figure 2 offers a summary of the American nuclear fleet and the energy markets that they operate in. Blue states are those with restructured, or deregulated, markets, and orange states are those that deregulated, but later suspended restructuring. The grey dots show operating nuclear plants, while the red dots show recently closed nuclear plants and green dots show nuclear plants under construction.

Figure 2. Electricity Restructuring and Nuclear Power Plants

29 nuclear plants operate in restructured markets, and a further 5 have been part of a restructured market in the past. 24 plants operate in regulated markets. Three additional are under construction, each in regulated states. Closures have taken place in one formerly deregulated market and three regulated states, although two of those three plants were operating as merchant generators that sold their power in nearby electric markets. Estimations of “at-risk” plants vary,33 Ibid, and Inside Climate News, 2013. but most at-risk plants currently operate in restructured markets.

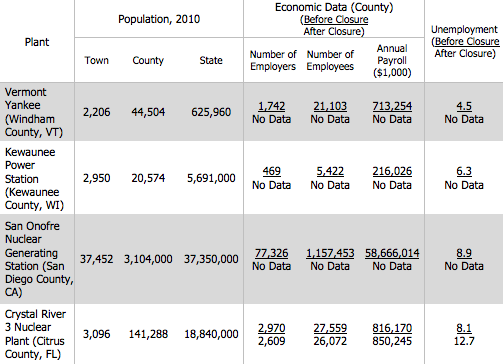

Nuclear power also offers economic support to local economies, and those impacts are perhaps more immediate to their communities than a closure’s impacts on the larger energy markets. Nuclear plants offer high-paying jobs that, in some cases, represent a large part of a community’s payroll. Table 1 shows economic data regarding the communities in which a nuclear plant has been closed, which varies from the small communities of Windham County, Vermont and Kewaunee County, Wisconsin, to the populous San Diego County, California.

Table 1. Counties with Closed Nuclear Plants. Crystal River’s closure was officially announced in 2013, but the plant has been out of operation since 2009. The Citrus County data displayed here is from 2007 and 2012, reflecting the time period before and after the operational outage, but also before the plant’s permanent closure in 2013.

The economic data surrounding the closure of nuclear plants is unclear at this time. The Census records economic data every five years, with the last collection occurring in 2012. Three of the four plants that have recently closed were shut down after 2012’s economic census, and we are therefore unable to assess any county or state changes in economic conditions. Further, even with before-and-after statistics, as with the Crystal River Nuclear Plant, it is difficult to say what direct impact the plant closure itself had on the surrounding economy. Greater macroeconomic conditions, such as the Great Recession, are more likely to have caused economic changes within these communities.

Unemployment figures have also yet to be released for most of these counties. We have presented unemployment data for the year before closure and year after closure, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has not released 2014 annual data for these counties at this time. Once BLS releases that data, a better picture of the economic impact of these closures may develop.

Where possible, we have collected and noted the number of employees and payroll at each closed nuclear plant. In some cases, these employees account for as much as 12% of the county’s employment, while in others, as little as 0.13%. Estimations of economic impact presented to regulatory bodies, such as state utility commissions, are also noted when available in the following section.

Case Studies

The four plants that have been closed since 2012 have distinct, yet similar, stories behind their closure. Two were shut down for explicit economic reasons; their operators both cited the low cost of competing resources as the primary reason for the closure. One of these plants also faced vociferous political outcry while its license renewal was considered. The other two plants saw technical malfunctions that were extremely costly. After attempts to repair these plants, their owners chose to close the plants rather than bear the repair costs.

Here, we will describe the conditions surrounding each plant’s closure, including any attempts made by responsible regulatory bodies to examine the plant’s future.

Vermont Yankee

The Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant operated as a merchant generator in Vernon, Vermont. The plant generated 604 MW, and supplied roughly 4% of New England’s total annual electricity supply.44 U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2013. Vermont Yankee shut down on December 29, 2014.55 Brattleboro Reformer, 2014.

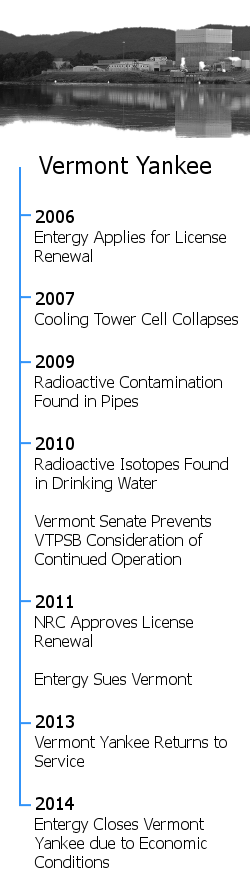

Vermont Yankee began operation in 1972, and employed 625 people when its closure was announced. The plant’s payroll was roughly $58 million.66 Daily Hampshire Gazette, 2014. A report submitted to the Vermont Public Service Board (VTPSB) estimated that keeping the plant running through 2032 would create an average of 1,088 more employees in Windham County, and 260 more employees across the rest of Vermont.77 Northern Economic Consulting, Inc, 2012. The plant applied for a license extension with NRC in January 2006. In 2010, the Vermont State Senate prevented VTPSB from considering the continued operation of the plant.88 U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2006. Vermont is the only state in which the legislature is able to vote on shutting down an active nuclear plant. The legislature must extend a “certificate of good” before a plant can operate, and the Senate did not approve Vermont Yankee’s extension.

Vermont Yankee Timeline

Vermont Yankee Timeline

The debate regarding Yankee’s certificate of good was contentious, as was the plant’s history. After the plant applied for its license extension with NRC, a series of events called into question the safety of the plant. A cooling tower cell collapsed in 2007,99 U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2007. radioactive contamination was discovered in underground pipes in 2009,1010 Barre Montpelier Times, 2010. and radioactive isotopes were discovered in nearby drinking water in 2010.1111 Vermont Department of Health, 2015. Protestors attached their concerns to these events, and statements from Vermont state officials put pressure on NRC’s license approval process.

NRC, however, approved the plant’s renewal in March 2011, and Entergy, the plant’s owner, subsequently sued the State of Vermont in April 2011. The appeal resulted in the reversal of the Senate’s measure because the Senate measure was focused on the safety aspects of Vermont Yankee.1212 Entergy Nuclear Vermont Yankee, LLC v. Shumlin The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 makes safety a federal responsibility, and the state has no jurisdiction over the safety of nuclear power plants. Vermont Yankee resumed its operations after the VTPSB entered into an MOU with Entergy in February 2013,1313 Vermont Public Service Board, Docket No. 7862. but, in August 2013, Entergy announced that the plant would close due to economic considerations. Entergy cited low power prices, high cost structure, and wholesale electricity market design flaws in its announcement of the closure.1414 Entergy, 2013. As conditions of Entergy’s MOU with the VTPSB, Entergy agreed to pay $10 million to promote economic development in Windham County, ensure site restoration, and pay $5.2 million for clean energy development.1515 Vermont Public Service Board, 2014.

ISO-NE reported that its reliability studies had concluded “that the regional power grid could be operated reliably without Vermont Yankee.”1616 ISO New England, 2013. Earlier studies had called this fact into question, but ISO-NE’s 2012 reliability analysis concluded that new system conditions, such as development of new resources, completion of transmission upgrades, and energy efficiency measures, made Vermont Yankee’s retirement unlikely to affect system reliability. ISO-NE expressed concern that the plant’s retirement would lead to a decrease in resource diversity, but noted that it does not have the authority to prevent a resource from retiring.

San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station

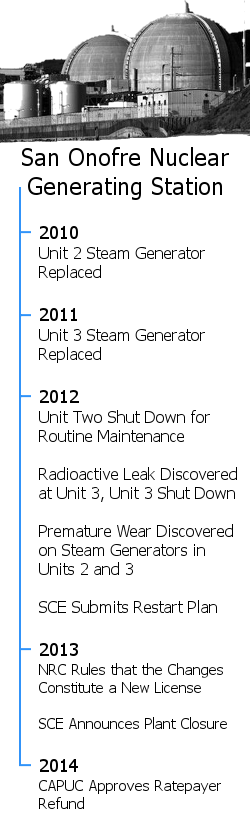

The San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) was owned by Southern California Edison (SCE), and included two reactors with a maximum capacity of 1127 MW each. SONGS is being decommissioned due to damage found in the plant’s steam generators. One reactor, Unit 3, experienced a radioactive leak in January 2012. The reactor was shut down, and inspections found premature wear on replacement steam generators installed in 2010 and 2011 in Unit 2 and Unit 3. The NRC ordered that Unit 2, already shut down for refueling and replacement of the reactor’s vessel head, and Unit 3 were not to be restarted until the cause of the wear was determined. SCE has since begun the decommissioning process for the plant.

San Onofre TimelineUnit 1 of SONGS generated 456 MW and was retired in 1992, while Units 2 and 3 generated 1127 MW each before their retirement. San Diego County is the largest county to see a nuclear plant shut down; SONGS employed just 1,500 of the county’s roughly 1.16 million employees.

San Onofre TimelineUnit 1 of SONGS generated 456 MW and was retired in 1992, while Units 2 and 3 generated 1127 MW each before their retirement. San Diego County is the largest county to see a nuclear plant shut down; SONGS employed just 1,500 of the county’s roughly 1.16 million employees.

SCE submitted a “Return to Service Report” to the NRC for Unit 2 in 2012, in which SCE proposed operational limitations in order to restart the reactor. The Atomic Safety and Licensing Board ruled that such changes would constitute a new license amendment, and SCE chose shortly thereafter to instead retire both Units 2 and 3.

The California Public Utilities Commission (CAPUC) began Investigation 12-10-013 to determine how the impact of the plant’s shutdown and decommissioning would affect rates in October 2012. In November 2014, a settlement was reached that allowed for ratepayer refunds and credits of roughly $1.45 billion. SCE also agreed to stop collection of its Steam Generator Replacement Project and to refund the collected costs of that project, while agreeing to a lower rate of return on prematurely retired assets. Ratepayers still paid for approximately $3.3 billion of power purchases associated with SONGS’ outage and the undepreciated net investment in SONGS assets. Further decommissioning costs will be recovered through the CAPUC’s Nuclear Decommissioning Cost Triennial Proceeding, Application No. A.12-12-012. As of November 18th, 2014, a proposed decision would approve roughly $4.1 billion for decommissioning SONGS 2 and 3 in that application.

In 2013 and 2014 Local Capacity Technical Studies, CA-ISO included scenarios in which SONGS was and was not able to operate. In 2012, CA-ISO completed transmission and voltage support enhancements near SONGS, and additional mitigations are being implemented through summer 2015. However, CA-ISO noted that pressures caused by the SONGS outage and retirement “will require close attention during summer operations – particularly during critical peak days and in the event of wildfires that could potentially force transmission lines out of service.”

Kewaunee Power Station

Dominion Resources shut down the Kewaunee Power Station in 2013. The 556 MW plant was purchased by Dominion in 2005, and had previously been owned by Wisconsin’s regulated Wisconsin Public Service. After the company sold the plant, the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin no longer had jurisdiction over the plant’s rates, and Dominion had to rely upon market prices for wholesale electric power to operate the plant.

In April 2011, Dominion announced that it planned to sell Kewaunee after it was unable to grow its Midwest nuclear fleet. Dominion claimed that Kewaunee’s PPAs were ending when wholesale electric prices were low, ensuring that new PPAs would make keeping the plant running uneconomic. In 2012, when no buyer was found for the plant, Dominion announced that it would close the plant. Dominion reserved $578 million for the plant’s decommissioning. Dominion employed 655 full time employees at Kewaunee Power Station, roughly 12% of Kewaunee County’s employees. Kewaunee County is the smallest county in which a nuclear plant has been closed, with roughly 20,500 residents.

After Dominion’s announcement of the closure, the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) conducted a reliability assessment and concluded that the closure of Kewaunee would not violate any reliability responsibilities. In February 2013, MISO announced that Kewaunee could be retired, and Dominion ceased generation at the plant in December 2013.

Crystal River 3 Nuclear Plant

The Crystal River nuclear plant was an 842 MW station in Florida. The plant stopped running after a refueling outage in September 2009, when the plant’s containment structure was damaged while Progress Energy attempted to replace steam generators within the plant. The plant’s owners, Duke Energy, have decided to decommission the plant rather than undertake the costly repair process.

Duke acquired the plant in 2012, when they purchased Progress Energy. The plant was previously purchased from Florida Progress Corporation, and had been regulated by the Florida Public Service Commission (FLPSC) throughout its history. The FLPSC approved a $288 million refund to customers to account for the cost of replacement power needed due to the Crystal River outage.

Crystal River offered 600 full-time jobs, accounting for roughly 2.1% of Citrus County’s employment. Progress had estimated that the repairs would cost between $900 million and $1.3 billion, and had intended to pursue the repairs. Duke, however, estimated the repair cost as between $1.5 and $3.4 billion, and decided not to repair the plant. Duke has permanently shut down Crystal River, and the plant is currently transitioning to a Safe Storage (SAFSTOR) condition.

Florida is not a participant in an RTO, but the Florida Reliability Coordinating Council (FRCC) examines the reliability impacts of plant closures. FRCC found that, in conjunction with the retirement of two coal-fired units at the Crystal River site due to mercury and air toxics regulations, the closure of the Crystal River nuclear plant could have an impact on system reliability. FRCC recommended extending the life of the coal plants in order to ensure system reliability in order to construct the needed transmission projects.

Trends and Differences in Approaches

State Utility Commissions

In the majority of these cases, the role of a public service commission is limited. Restructuring has removed generating resources from the commission’s purview, and even a vertically integrated state does not offer its commission the jurisdiction to decide whether or not a specific resource runs. State regulators are, instead, economic regulators, who ensure that energy costs are just and reasonable. Without further mandate from state legislatures, commissions do not have the authority to prefer one particular resource.

The Crystal River plant was closed in the face of costly repairs, not economic pressures. The FLPSC worked to limit some of the plant’s impact on ratepayers by approving refunds, and Duke had to recover the cost of the damages through insurance claims, not rates. In this situation, repairing the plant would have required up to $3.4 billion of additional ratepayer money, which made keeping the plant in the rate base prohibitively expensive.

The San Onofre plant was also closed due to repair costs. Similarly to the FLPSC, the CAPUC ensured a refund to ratepayers. In both cases, ratepayer advocates have noted that the refunds are unlikely to cover all of the associated costs of purchased replacement power. However, returning the plants to service would also have been expensive for ratepayers. These closures speak to the age of the United States’ nuclear fleet, and the danger that time represents to nuclear power plants.

The remaining closures at Vermont Yankee and the Kewaunee Power Station are distinct because both plants were operating as merchant generators. These plants were subject to competition with wholesale electricity prices, and found themselves unable to operate in these economic conditions. This threat extends to other nuclear plants, particularly those who operate in deregulated energy markets. These plants have no mechanism for cost recovery from their states’ commissions, and must compete in a market that they insist does not properly compensate them for their advantages, such as reliability and carbon-free emissions.

State Legislatures

While state utility commissions have not been particularly active in nuclear retention decisions, state legislatures have adopted a variety of stances towards nuclear power. Seven states have adopted legislative incentives designed to promote nuclear construction or generation. However, 13 states have placed additional restrictions on the creation of new nuclear plants. These incentives are summarized in Figure 5, below.

Figure 5. State Legislative Incentives and Nuclear Power Plants

State incentives that encourage nuclear power vary between the states. Some states offer tax benefits to nuclear power; Alabama does not tax nuclear fuel, and Kansas exempts new nuclear generators from property taxes. Kansas also allows for the cost recovery of nuclear studies undertaken in order to examine the construction of a new nuclear plant. Indiana and Ohio include nuclear energy in their clean energy and renewable energy definitions. Finally, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina have each amended their regulatory processes to ease the cost recovery process for new nuclear plants.

The states that have adopted nuclear disincentives have largely done so on the requirement that a waste disposal solution is discovered. California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Oregon, West Virginia, and Wisconsin will not allow new nuclear to be built until viable waste disposal options are found. Wisconsin also requires that a new nuclear plant prove that it is economically feasible. Hawaii, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont require legislative approval for new nuclear plants, while Maine, Massachusetts, and Oregon require voter approval. Minnesota has banned new nuclear plants.

Few of these policies affect already-constructed plants. Alabama, Indiana, and Ohio do offer incentives to running plants, but each of the negative incentives is placed on potential new nuclear plants. Nonetheless, three of the four recent closures have occurred in states that have adopted negative nuclear incentives. The final closure occurred in Florida, whose policies have encouraged new nuclear development. New nuclear appears to be linked to such positive incentives, as two of the three plants under construction are located in states with those policies.